The Romanian Parliamentary Vote: From Protest to Protest

In the context of the region, the Romanian political landscape is quite a special case, which presents an interesting, even counterintuitive, picture. On the face of it, Romania is a country with improved anti-corruption results, the fastest growing economy in the EU[i], an increased civil society mobilization score, with an ethnic minority president and no far right parties in a center-left dominated parliament. This is not what one would expect in Eastern Europe these days. Considering its past and its social and economic situation, one might be inclined to think that Romania would struggle with populist, anti-establishment challenges, similar to what currently propagates throughout the region. But that does not mean that populism and strong social cleavages are not elements in the mix of Romanian politics; it’s just a different dynamic at work.

Nevertheless, the parliament is perceived as one of the most corrupt institutions, where, at one point 82 of the 588 member legislature (2012-2016) had been found guilty or were under investigation for corruption charges by the National Anticorruption Directorate[ii]. So why did Romanians choose to support the Social Democratic Party (PSD) despite its past record and reputation? The Romanian social democrats remain a highly polarizing political force; known for their leftist promises for the lower income segments (i.e. wage and pension increases) and for a stream of high-profile corruption cases such as jailed ex-prime minister Adrian Nastase or its current leader, Liviu Dragnea’s sentence for electoral fraud. Almost a year from the Colectiv fire, the ensuing anti-corruption protests and the optimism for change after Prime Minister Victor Ponta’s resignation, does this mean it’s back to business as usual?

The Results

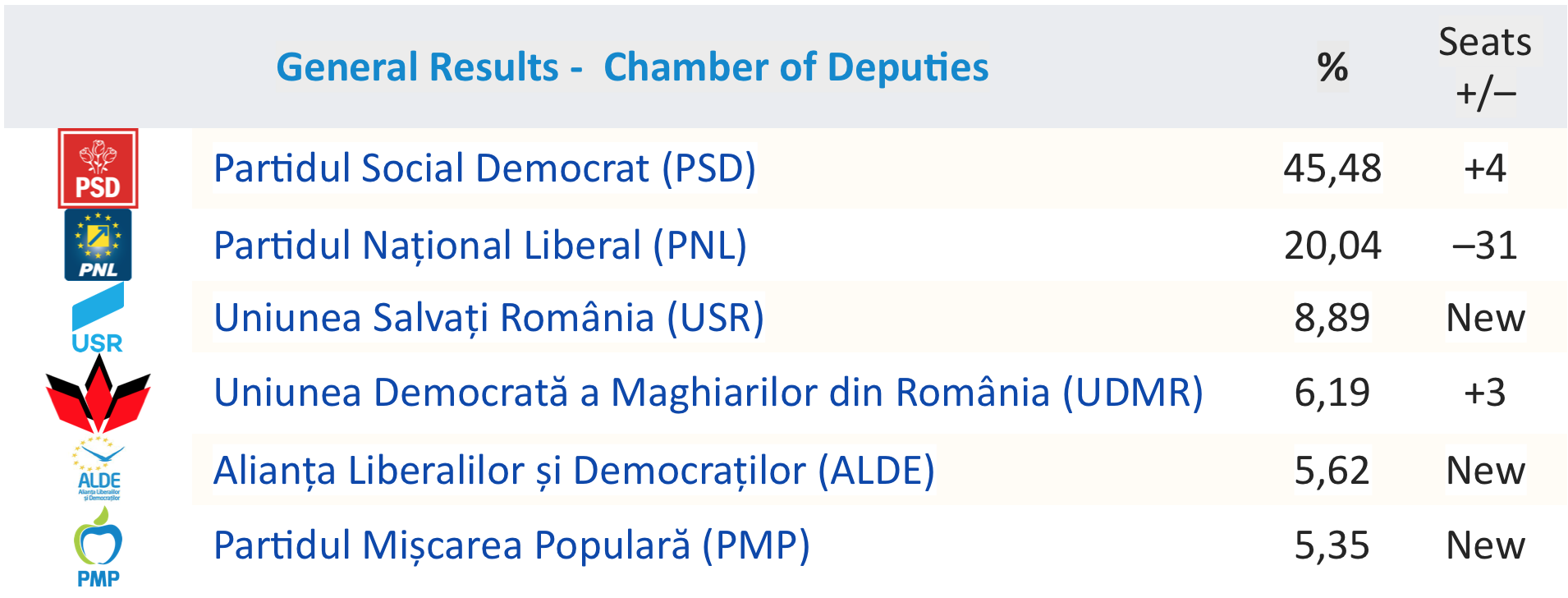

After a polarizing campaign, with identitarian and populist tendencies, PSD emerged as the clear winner of the latest Romanian parliamentary elections, with 45,5% of the vote; leaving second-placed liberals (PNL) far behind on 20%. Corruption issues, it would seem, took second place to salaries and pensions, in a country where one in four live in poverty. Four other parties managed to earn enough votes over the 5% threshold (see table below). Apart from the Hungarian minority’s party (UDMR) that received a predictably comfortable 6,2%, technically three new parties entered parliament. However, only the Save Romanian Union (USR) is a political outsider, gathering a surprising 9% (more on that below). The other two new parties are offshoots from other large parties and run by well-known political figures. The Alliance of Liberals and Democrats (ALDE) is run by ex-Prime Minister Tăriceanu, an ex-PNL member turned PSD ally. Lastly, the People’s Movement Party (PMP), formed in 2014 by then-President Traian Băsescu following the break with the Democratic Party, barelly made it pass the threshold.

Source: BEC

Building on its local elections success in June, PSD now dominates both the legislative and executive branches. While the party had its share of successful elections since 1990, this is the closest it came to an overall majority on its own. A resounding win indeed. On the other hand, commentators lamented the low turnout rate of just 39,5%. While technically the second lowest parliamentary election turnout since 1989, it just adds to the streak of low scores registered since the first time these elections were desynchronized from the presidential vote in 2008[iii]. In any case, these results look to produce, at the minimum, a politically tense and unstable period, especially in the relations with the presidency and the judicial system (especially the National Anticorruption Directorate); all this on the background of an increasingly volatile international context. That is the expectation, at least, if one judges by this December’s government formation and Prime Minister nomination proceedings and the latest attempted changes to the anti-corruption laws by the executive.

The campaign

A broad explanation for the apparently uneventful election (i.e. a low turnout, status-quo-preserving Eastern European legislative election) is evident in the electoral campaign and its ensuing dynamics. While the parties campaigned heavily on issues such as corruption, the judicial process, salaries and pensions, immigration, Euroscepticism, the polarization around the main political forces was not reflected in the final result, making the PSD win look easy.

Two party clusters polarized around the main parties on the center left (PSD) and center right (National Liberal Party or PNL) dominated. While there were no large official coalitions in the campaign, the smaller parties were gravitating around these two opposing parties. While indeed the so-called left-right political spectrum in Romania is either understood to have a different dynamic or not to exist at all, in this election these were the two main choices: PSD (and their junior coalition partner ALDE[iv]) and PNL, which backed the technocratic ex-prime minister Cioloș, as a campaign brand. All parties catered to their own electorates, with many identitarian and populist elements defining the election tone and the so-called party ideologies.

Regarding the left-right Romanian particularities, for example, even through PSD is in the same European political family as the other large social democratic parties (e.g. the German SPD or the Swedish Social Democratic Party), it is ideologically very far from those. With an arguably strong neoliberal track record, traditionally close to the Romanian Orthodox Church, against immigration and same sex marriage, PSD, some even have said, looks more like a Romanian version of the American GOP, rather than a European social democratic party[v].

As their main opponent, PNL led an anti-corruption campaign supporting the technocrat Cioloș for prime minister. The liberal campaign was also strongly focused on an anti-PSD message. A telling example of this was the choice of party slogans. While PSD had the slogan “Dare to believe in Romania”, PNL took on the same slogan adding a reference to honesty (“Dare to believe in Romania, led by honest people”)[vi], all in an attempt to draw attention to its opponent’s corruption record. This in turn led to the feeling that PNL is not a choice in itself, but positioned as “the only alternative” against a corrupt PSD status-quo. Also, it’s worth remembering that PSD returned to power in 2012 in a coalition, which included the liberals (PNL) on an anti-austerity program.

The latest parliamentary campaign included strong populist tendencies, coming from established parties, throughout the entrenched media, and not just the far right. Of course, what’s important here is the extent of ‘utilitarian populism’ (i.e. the use of populist discourse to serve electoral purposes). Another issue critically in need of further analysis is that this campaign should also raise serious questions about press freedom and its independence in Romania.

Regarding the far right and its strongest exponent in this election, it’s interesting to note that the United Romania Party (PRU) is a new party founded by an ex-PSD member. In its campaign it supported ex-prime minister Victor Ponta[vii] (a PSD member) and was generally regarded as a PSD satellite party. This actually is one of the strongest contenting explanations on why populist, far right movements did not pick up in Romania: the main parties already long occupied that space and run their campaigns accordingly.

So business as usual?

A surprise breakthrough was the newcomer Save Romania Union (USR), formed a few months before the election. This is a new development for Romanian politics, as USR tries to directly relate itself to the Roșia Montană movement (and the ‘United We Save’ campaign). This in turn means that for the first time, activists are MPs and already have shown some signs of increased social media communication and other types of pressures on the ruling coalition in parliament. USR had however, a rather curious platform, with an urban-focused mix of anti-corruption and anti-establishment elements, with no clear left or right direction and a strong support for the technocratic government. USR got close to 9% of the vote, mostly from young urban progressives as well as other disillusioned liberal voters.

Perhaps the main distinction of the latest election campaign and the general Romanian political landscape is that active populist tendencies abound, but without strong ideological lines (such as we are witnessing in the region). In a system where the rules tend more to be renegotiated rather than respected it’s all about coming to power and riding any “wave” necessary in the process.

Tensions ahead?

Even before the election results, tensions were looming on the horizon, especially regarding the question of the prime minister nomination. In an unusual move PSD did not have a clear campaign proposal for the executive chief. The favorite however, was always Liviu Dragnea, the president of PSD. His problem however, was that he is currently serving a two-year suspended jail sentence for electoral fraud in a previous election. President Klaus Iohannis, who can constitutionally reject any candidate that he does not see fit, vowed to stop anyone having a criminal record from leading the government, in line with existing legislation on the matter. After a tense couple of days after the results, Dragnea said that he “will make a proposal you can’t refuse”. That proposal was for the first female and first Muslim prime minister, Sevil Shhaideh. A surprising move after a campaign in which Iohannis and Cioloș were both attacked for not being “real” Romanians by the PSD-leaning media. In any case, the president did not give out any reason for his refusal to nominate the proposed candidate, although there was speculation that it may have been related to her Syrian husband’s background. Right after Christmas, Romania seemed to be headed towards a serious political crisis after rumors started to spread about the president’s impeachment by the newly elected parliament or even early elections (in case of a second nominee refusal from the president). Finally, President Iohannis accepted a second proposal from PSD and 43-old Sorin Grindeanu became Prime Minister, with Sevil Shhaideh, the first proposal, taking the Vice-Prime Minister position in the current Romanian executive. Crisis averted.

So is it now business as usual? Well, the latest developments show that, in certain regards the answer, at least concerning the new political majority, is yes. Citing a need to align the criminal code with recent constitutional court rulings and also help ease the burden of Romania’s overcrowded prisons, the PSD-led executive aimed to grant prison pardons and decriminalize some offences through emergency decrees (not regular parliamentary procedures), weakening the anti-corruption drive. President Iohannis, in a surprise move[viii], went and presided over the government meeting, and it would seem, that the proposal has been postponed for the moment. Since then, tens of thousands protested in Bucharest and other main cities against the government decrees. The protests peaked in the 20-22 January weekend and, at the time of writing, seem set to continue. That Sunday, President Iohannis joined the protesters in Bucharest, saying: “A gang of politicians who have problems with the law want to change the legislation and weaken the state of law. Romanians are rightfully outraged.” All this feels eerily similar to the 2013 protests, which started from the attempted mining law change (affecting Roșia Montană) and the so-called “black Tuesday”.

This is a first sign that apathy did not completely overwhelm Romanian society. The presidency and the judicial branch (especially the National Anticorruption Directorate) are the only non-aligned so-far. Disbanding the National Anticorruption Directorate (or at least weaken it) would probably be a much-desired outcome for PSD. It remains to be seen what reaction the people would have, but also Brussels, in a game where image seems to still matter for the moment. It would seem, that tensions and political crises remain an increasingly probable state of affairs in the coming period.

[i] https://www.agerpres.ro/english/2016/10/04/imf-romania-to-have-highest-economic-growth-in-europe-in-2016-and-2017-17-30-16

[ii] Other, more recent reports put this number slightly lower at the end of the mandate in December 2016, with around 35 members of parliament having legal problems: http://www.ipp.ro/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Bilanț-al-principalelor-aspecte-care-au-marcat-activitatea-actualului-legislativ-în-perioada-2012-–-2016.pdf

[iii] The turnout in 2008 was the lowest ever recorder with 39,2%, then rising slightly in 2012 to 41,7%. For comparison, in 2004, the last time both parliamentary and presidential elections were held at the same time, voter turnout was 58,5%.

[iv] ALDE – Alliance of Liberals and Democrats, officially a center-right party is headed by the ex-prime minster Tariceanu, received 5,6%, barely above the minimum 5% threshold.

[v] Indeed, both the Prime Minister Grindeanu and the PSD chief Dragnea, have attended Trump’s inauguration ceremony in January 2017.

[vi] http://www.nineoclock.ro/pnl-slogan-for-the-elections-dare-to-believe-in-romania-led-by-honest-people-striking-similarity-with-the-message-already-launched-by-psd/

[vii] Ponta also declared how close the aims of both parties are: http://www.mediafax.ro/politic/victor-ponta-psd-este-un-partid-mai-timid-ne-place-ca-cei-de-la-pru-spun-ceea-ce-gandim-noi-16018270

[viii] It was only a rumour that the governmental meeting was going to decide on the ordinances and in a surprise move, the President, for the first time in his mandate, decided to attend and to preside over the government meeting (as the constitution allows) and to also discuss the potential legislative changes, saying: “There are two elephants in the room and no one is talking about them: the emergency pardoning decree and the decree that changes criminal codes.”