Slovakia, a Country of Disillusioned People

The Slovak Republic is a small Central European country that has never been in the spotlight from the European perspective. And even now, it stands at a crossroad, choosing whether it will remain a consolidated democracy or transform into a regime more dangerous and autocratic than Orbán’s Hungary, driven by backlashing tendencies, pro-Russian narratives, and xenophobic and radical forces. The early parliamentary elections that will be held on 30 September 2023 will destroy the status quo of not picking a side, drawing them closer to the Byzantine way of thinking and doing politics.

In other words, in recent years, Slovakia has witnessed significant political changes demanding an end to corrupt politics, but in reality, the system was rooted inside society as a whole due to its lack of transparency and questionable ethical standards. Those narratives and views were also incorporated into politics through unscrupulous political practices, intrigues, and manipulations, including power struggles, political favoritism, practicing nepotism, and making decisions through closed-door negotiations. Current trends and tendencies in society point in that direction.

The Radicalization of Robert Fico

And who stands on the barricades of this backlash? You would probably point to the right fascists in the Slovak parliament (Kotleba People’s Party – Our Slovakia, Republica – newly formed subject from former members of the Kotleba party) or those hardliners in the conservative camps (Christian Union Party, Life – National Party). All of them may give fuel and drive the country away from liberal democracy. And who is hijacking the country away from the West, Europe, and democracy is the former prime minister and former formal supporter of Europe and the West, Robert Fico, the leader of the social democrats.

Is it surprising? In the eyes of the West, yes, as it has been with Central European politics too many times. Robert Fico is the master of storytelling. In 2012, he wanted to protect Slovaks from the chaos after the collapse of the right-wing government of Iveta Radičová; in 2016, he tried to protect them from refugees and migrants. In 2023, the degree of radicalization being witnessed echoes the levels seen in the 1990s. Now Fico is spinning the roulette more perfidiously and radically than ever; even Viktor Orban’s political style is looking decent and more diplomatic compared to the Slovak colleague. He is creating stories about Russian friendship, the perverse West, liberal mercenaries paid by American Jews, and constant threats by external forces.

The logical question would be, why are you so sure this would work? In the last weeks, we have published and discussed two public opinion polls led by us – Bratislava Policy Institute (BPI) – that focus on European themes such as migration, the rule of law, Next Generation Europe, and the climate in the perceptions of Slovaks.

The End of the Democratic Consensus in Slovakia?

My first observation of the data we received in the last two public opinion polls was precise: Slovakia is anomic. Which, in between words, means that the society is feeling disconnected from the social structure and lacks a sense of belonging. It is experiencing a higher level of political instability, lack of trust in political institutions, and lack of social cohesion, accompanied by high fragmentation and polarization of society. Additionally, economic inequality is prevalent, with a significant wealth gap between the rich and the poor, exacerbating social tensions and feelings of injustice. The lack of effective social support systems and inadequate healthcare services further contribute to a sense of anomie, as individuals struggle to meet their basic needs and lack a sense of collective solidarity.

Many of us, scholars from academia and research institutions, internally battled to name it and discuss it, even though we felt that those warning signals, such as apathy, distrust towards social norms, and disillusionment, were present long ago. But still, the country was able to cope with these negatives in a way that others would be ripped apart. The key to success was a relatively stable international environment and an environment without a dramatic crisis. The last few years have changed this consensus, and relatively stable and established democracies have dropped to their knees, so why should we be surprised that a country carrying these societal illnesses for a very long time should be after a global pandemic and a war in Europe stable and healthy?

Slovak society faces its biggest challenge since 1989, when it became a democratic political system. The erosion of democratic institutions is more visible than ever, and the polarization of society fuels the authoritarian tendencies of competitive political actors, accompanied by a decline in civic engagement and disconnection from political life. Slovaks are generally pessimistic about the current state of affairs in their society, with only 18% feeling that the country is going in the right direction, and only one-third of them agree that most people can be trusted. This pessimistic view is accompanied by the feeling that political efficacy is very low; according to our latest public opinion poll, only 19.3% of Slovaks believe they can influence politics.

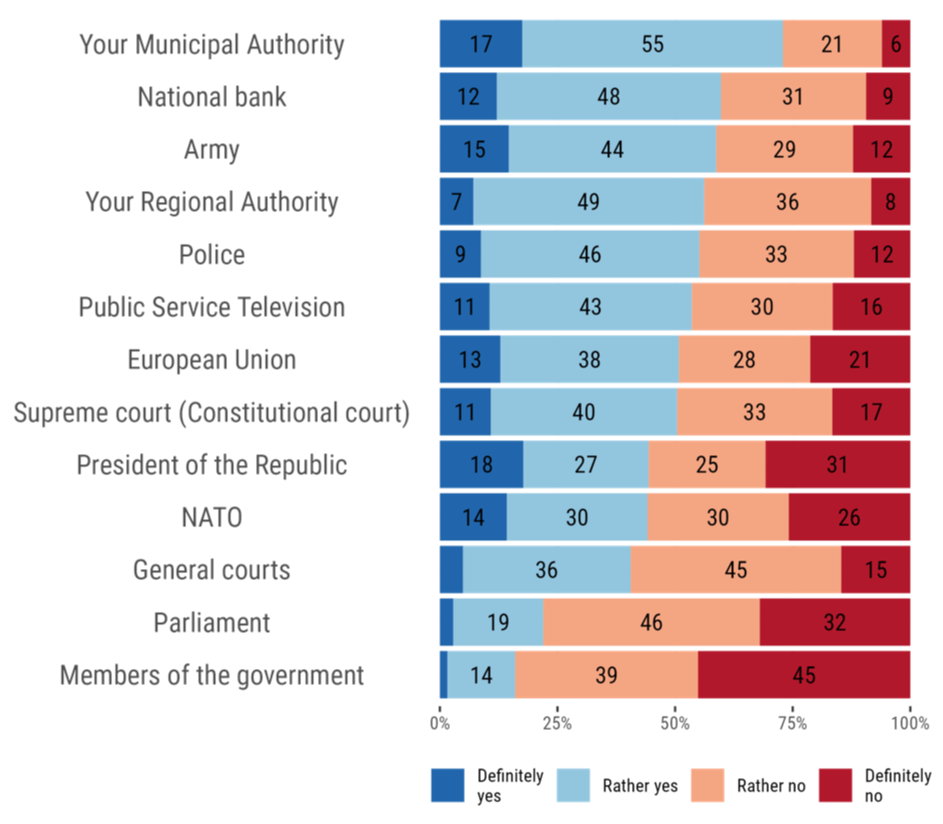

Table 1: The overall trust of Slovaks in institutions

When people feel disconnected and numb, they are less likely to engage in political activities, which may weaken their faith in the democratic system and commitment to democratic principles. Similar trends are also visible among Slovaks and their overall trust in democratic institutions. The disillusionment with the existing democratic institutions could manifest as democratic backlashing, which is present in Central European countries, and the rise of authoritarian tendencies that may be more susceptible to the allure of strong leadership promising stability and order.

The anomic tendencies and erosion of public trust also mirror the lack of social cohesion, the absence of moral responsibility, and general alienation from the democratic system. To illustrate the anomie, I will give you just a few examples that perfectly describe the state of the mood of Slovak society three months before the election.

- 71.7% of Slovaks believe that you can succeed in business only when you have political ties.

- 75.5% of Slovaks believe corruption is part of our culture.

- 90.6% of Slovaks believe that politicians are involved in corruption.

- 28% of Slovaks believe that courts are independent of undue influence.

- 42% say that a corrupt high-ranking police officer ends up in jail when caught.

Only Doom and Gloom on the Horizon?

The upcoming early parliamentary elections will disrupt the traditional status quo and pave the way for non-democratic forces. Former prime minister Robert Fico, once a supporter of the EU and the West, is now harnessing radical narratives and exploiting societal fears to push an agenda that distances Slovakia from liberal democracy.

The country’s anomic state and the potential for democratic backlashing in Slovakia could also have broader implications for Europe. Slovakia’s trajectory towards a more autocratic regime, driven by pro-Russian narratives, xenophobia, and radical forces, could set a precedent for other Central European countries. The region has witnessed similar backlashing movements, and Slovakia might become the following exemplar of this trend.

Addressing the societal illnesses of anomic tendencies, erosion of trust, and disillusionment is crucial for Slovakia to maintain a consolidated democracy. Rebuilding trust in democratic institutions, fostering social cohesion, and engaging citizens in political life are essential steps to prevent further democratic decline. The international community, including the EU, should closely monitor and support Slovakia’s efforts to strengthen democracy and address the underlying causes of anomic society.

The future of Slovakia hangs in the balance, and it is crucial to address these challenges to ensure a democratic and prosperous future for the country and to prevent its negative impact from spreading to the broader European context.

Sources:

RevivEU Summary Report 01

RevivEU Summary Report 02

Cover picture: National Council of the Slovak Republic. ©WikiCommons